Japanese pornographic films (referred to in Japan as “AV”, an abbreviation of “adult video”) are known worldwide for their high production values and innovative concepts. However, a Japanese law established in 2022 is currently threatening to drive the production of AVs underground, depriving industry members of financial and professional opportunities. This article covers the law’s impact, as well as one campaign that hopes to amend it.

Disclaimer: This article contains researched information and the author’s personal opinion. June Lovejoy, an AV performer cited in this article, is the owner of Tokyo Love District.

What is the new AV law?

Enacted by the Japanese government in June 2022, the Law to Prevent and Assist AV Performance Victims (AV出演被害防止・救済法 in Japanese) has established several new rules in regards to the production and distribution of AVs:

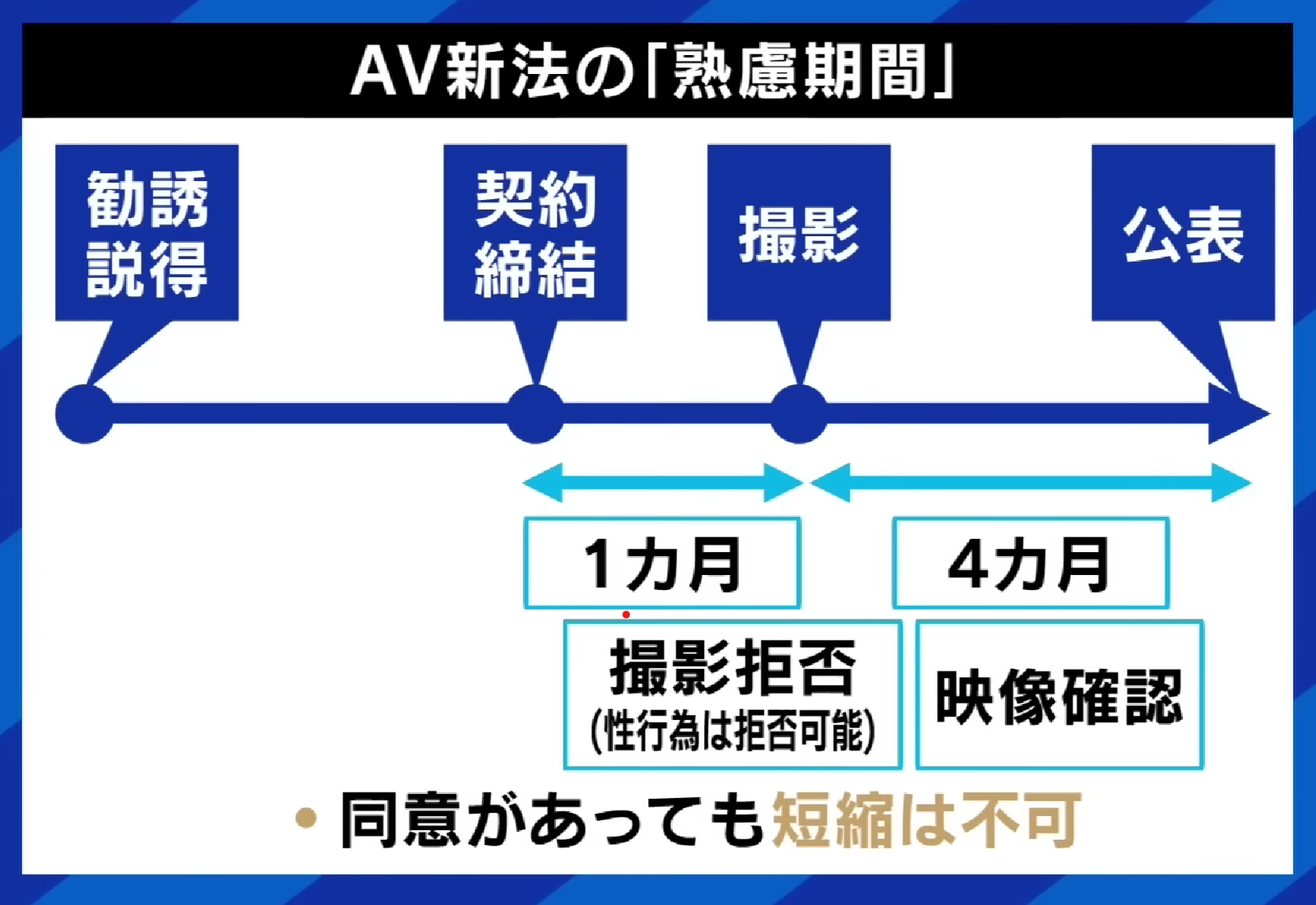

- Once a performer signs a contract to appear in an AV, there is a mandatory one-month cooldown period before filming, during which the performer reserves the right to decline to appear in the film.

- Upon the completion of filming, there is an additional mandatory cooldown period of four months. During this time, the filmed footage is reviewed, and the performer is able to have the film’s release canceled if they so wish.

- For one full year following the production of an AV, performers reserve the right to break their contract and halt the film’s distribution for any reason.

The following graphic, displayed during a March 13th ABEMA Prime segment focusing on the new AV law, illustrates this timeline:

There is no currently no way to bypass or truncate the cooldown periods during production, even if the performer expressly wishes to do so. Furthermore, even after a film’s release is publicly announced, the pre-order window prior to the release itself often lasts for up to a month. This lengthening of the production process is an obstacle for AV studios aiming to produce films that are in line with social and seasonal trends. It also makes it challenging for performers to promote their work to their fanbases.

The campaign to revise the law

The campaign to revise the new AV law is being led by the Association to Consider the Optimization of the AV Industry (ACOAVI; AV産業の適正化を考える会), a group spearheaded by U.S.-based Japanese adult actress Marica Hase and AV director/author Hitoshi Nimura. Former and current AV industry professionals have rallied in favor of the campaign. It has also gained the support of politician Satoshi Hamada of the NHK Party, as well as Ōta Ward assemblyman Minoru Ogino. Hamada was the sole member of Japan’s House of Councillors to vote against the enactment of the law in 2022.

Note: The group’s official English name is the Associate to Consider the Appropriation of the AV Industry [sic]. The author has used an edited name in this article for the sake of clarity.

ACOAVI has launched a Change.org petition, linked below, in favor of revising the new law and adjusting the length of the cooldown period for productions where all parties consent to do so. Upon reaching 100,000 signatures, ACOAVI intends to present the petition to the Japanese Diet. As of this writing, the petition currently has 21,729 signatures. The law contains a clause stating that its stipulations must be reviewed within two years of its enactment, giving lawmakers until June 2024 to revise the law.

The new law’s impact on the industry

During ACOAVI’s February 23rd protest rally in Ginza, AV industry members and their supporters were notably joined by director and television producer Terry Ito.

Ito echoed concerns voiced by industry professionals, stating:

「AV新法は2年前に、深く精査しないでできてしまった。実際にできてみると、新人と何年もやっている方が同じ扱いになっている。」

“The new AV law ended up being enacted two years ago without any thorough investigations of the industry. Now that it’s in place, new performers and performers who have been working for years are being treated the same.”

On the surface level, newcomer and veteran performers receiving the same treatment can be interpreted as a positive outcome. However, due to performers’ aforementioned inability to skip or shorten the cooldown periods during production, experienced performers who have no doubts about appearing in adult content are no longer able to work freely and efficiently.

This point of veteran actors’ work being restricted is reiterated by one of the AV industry’s top male stars: Shimiken.

During an interview with Career JUMP posted on YouTube on February 29th, Shimiken announced that after over 20 years of working as a performer and director, he currently considers himself semi-retired from the AV industry. He identified the new AV law as being part of his motivation to semi-retire, stating:

「…台本に書いてないことはやったらダメっていうのが今すごく言われていて、予定調和のものしかない。今までのAVっていうのはイレギュラーな部分がすごく楽しかったのに、それがなくなった…規制がクリエイティブを生むなとは思ってたけど、生まれない規制もあるんだな…」

“We’re being told that we can’t do anything that hasn’t been written in the script, so the only films made now are the ones that play it safe. Working in the AV industry up until now, the out-there bits of filming have been so much fun, but we don’t have those anymore. I’d always thought that limits could birth creativity, but these limits haven’t been doing that at all.”

Thus, the new AV law has deprived experienced, knowledgeable talent of opportunities to improvise, innovate, and produce content that goes beyond industry conventions.

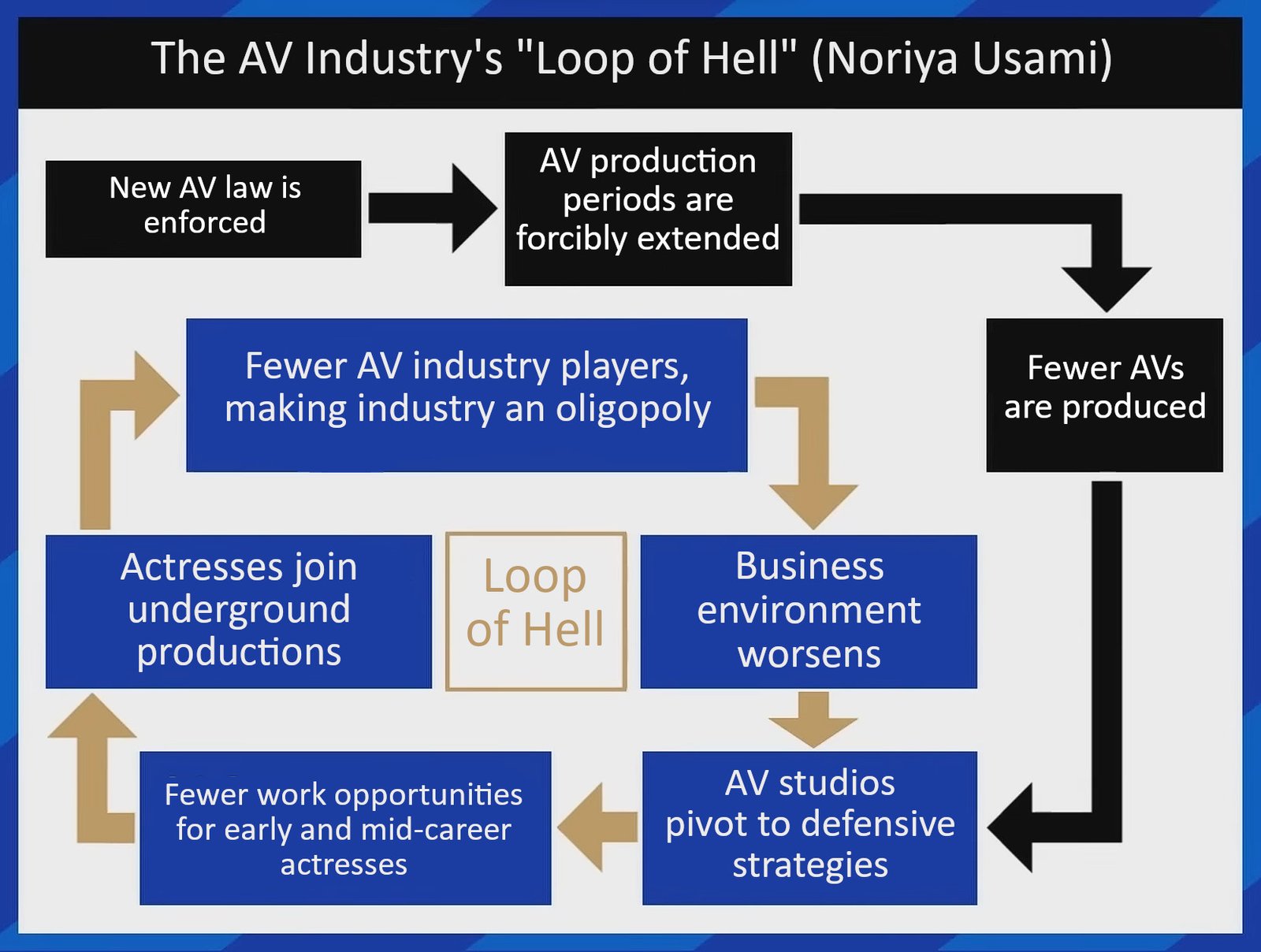

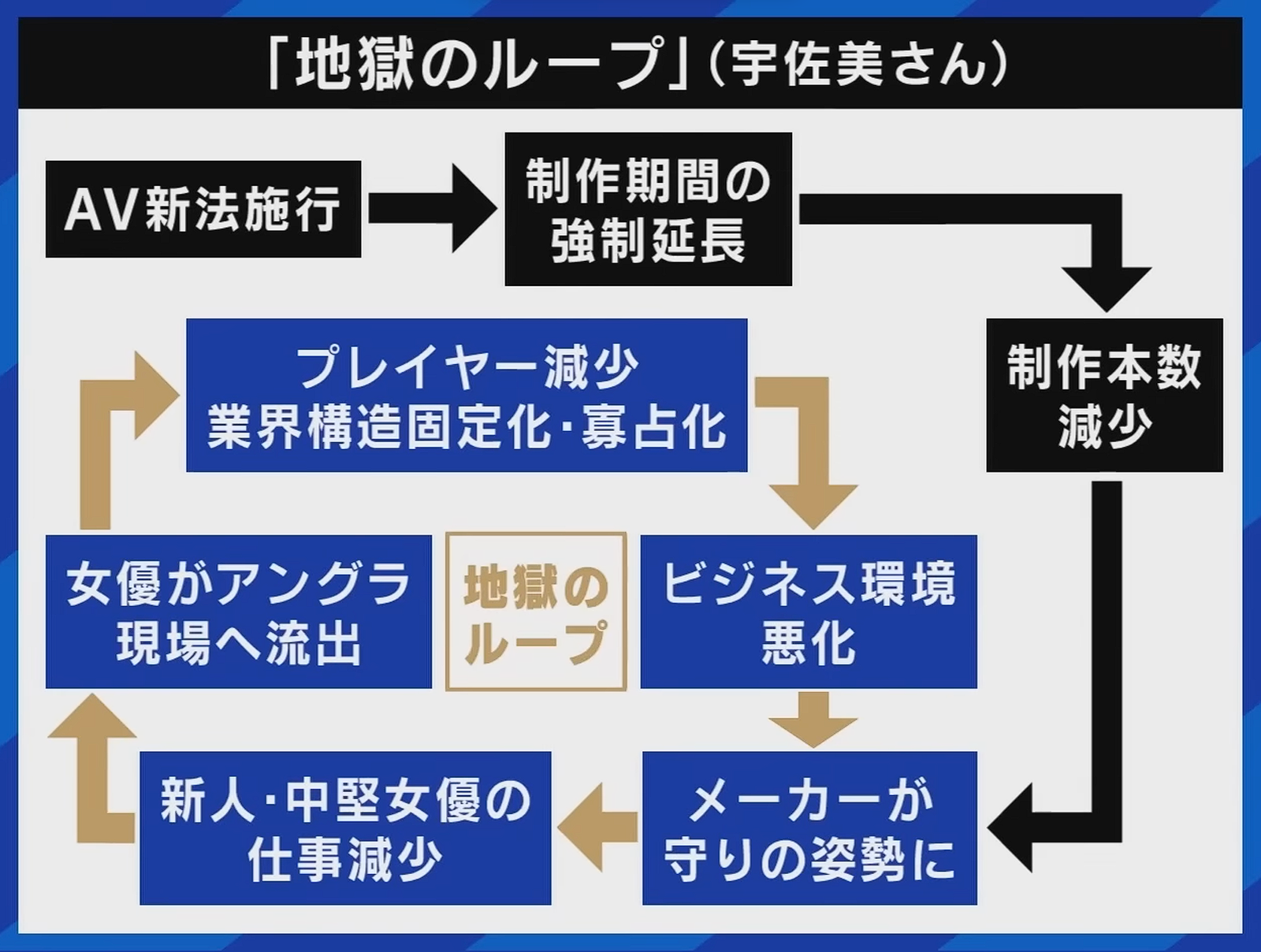

During the aforementioned ABEMA Prime segment, analyst Noriya Usami outlined the current tumultuous state of the AV industry with the following graphic:

Even prior to the enactment of the new AV law, the threat of underground productions has consistently loomed over the AV industry—unpredictable environments that may offer performers more take-home profits (as most performers are signed to agencies that take a cut of their pay for professional shoots), but are under no obligation to follow industry standards.

In order to be considered fully legitimate players in the AV industry, production companies are required to register with the IPPA (Intellectual Property Promotion Association; 知的財産振興協会), an organization that monitors AV piracy and ensures that their content is in line with Japanese legal requirements. IPPA oversees not only the production and distribution of AVs, but also that of adult video games and other forms of media.

While not all independent AV producers are bad actors, the rise of underground, unregulated AV productions outside of the IPPA’s reach poses risks to the safety and livelihoods of performers who sign on to film for them. Films produced underground are often uncensored, making them illegal to distribute in Japan. Participants in such productions face arrest if identified.

Former AV actress Ami Kasai describes the aftermath of appearing in an uncensored, underground AV in this X (formerly Twitter) post:

“When I appeared in an uncensored AV, I was told that I’d be fine, but I ended up getting arrested. That film was distributed illegally from overseas, so it won’t be deleted. My agency said that they would have all of the articles [about Kasai’s arrest] deleted, but they didn’t, and then they ran off with my pay. I’ve suffered more than a lot of AV actresses, but let’s push for the revision of the AV law so that no one else has to go through what I did.”

ACOAVI members also expressed their concerns about the new AV law in a symposium on February 20th that also included legal and economic experts and politicians. Members of the LDP, JIP, DPP, and the NHK Party were present. During the symposium, in reference to a Q&A handbook about the new law authored by several of the politicians who enacted it, attorney and legal scholar Yusuke Taira stated:

「営業の自由、職業の自由、それから表現の自由。一言も出てきません、これ。200ページぐらいある書籍。1文字も出てこない。職業という言葉も出てこない。」

“The freedom to conduct business, the freedom to choose your career, and freedom of expression. Not a word of these concepts is mentioned in the nearly 200 pages of this publication. Not one word. The word ‘career’ is never used.”

Article 22 of the Constitution of Japan states that all Japanese citizens have the right to “…choose [their] occupation to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare.” The fact that the new AV law fails to acknowledge the autonomy of AV industry professionals calls into question whether it can adequately protect their rights and best interests.

Effective advocacy for AV industry professionals must include and value their voices. One such organization that has succeeded in doing this is the AV Human Rights & Ethics Organization (AV人権倫理機構), established in 2017. The group consists of legal experts and industry allies who work to ensure that performers remain informed of their rights throughout the AV production process. Prior to AV shoots, the organization interviews performers and confirms that they are appearing of their own will. They also assist performers who wish to have their films removed from online marketplaces.

Despite the AV Human Rights Ethics Organization and the IPPA not strictly being part of the AV industry itself, the fact that they have taken the effort to involve themselves closely with industry professionals have allowed it them to become trusted allies in ensuring the safety and satisfaction of performers. Even prior to the enactment of the new AV law, such organizations have made a lasting positive impact within the industry.

On August 8th, 2021, when asked online about consent during the AV production process, freelance AV performer and cosplayer June Lovejoy said:

“…We have to consent to everything on camera while reading the entire contract out loud and signing it. If we don’t, we don’t even get to film. If the studio doesn’t have that video with the person consenting and reading [and] signing the form, they can’t produce the film. There is also a contact information form on every contract with groups like the AV Human Rights [& Ethics] Organization listed. We also have to complete a check sheet stating that we weren’t coerced, we are aware this is an AV film, and so forth. If you don’t consent, you don’t film.”

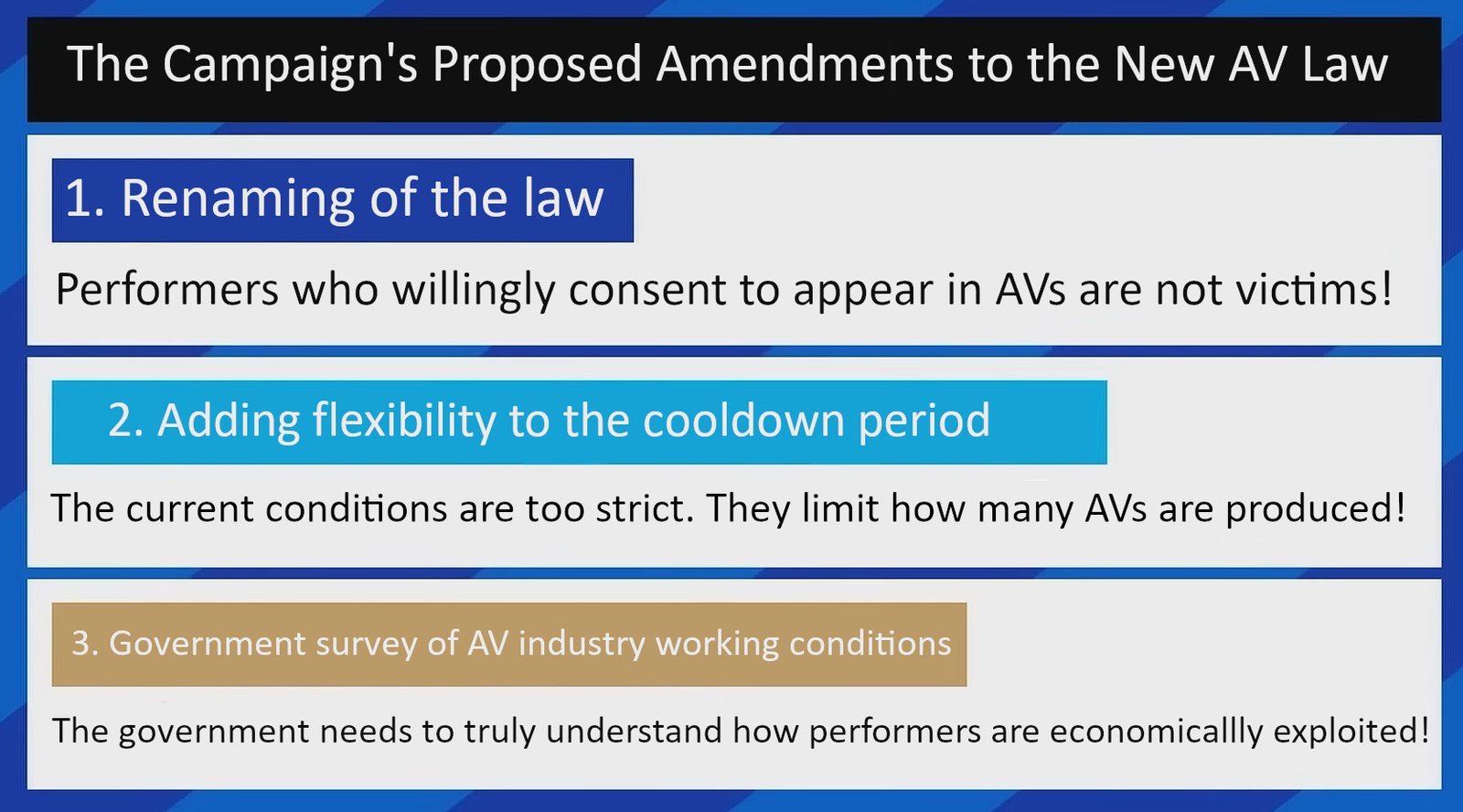

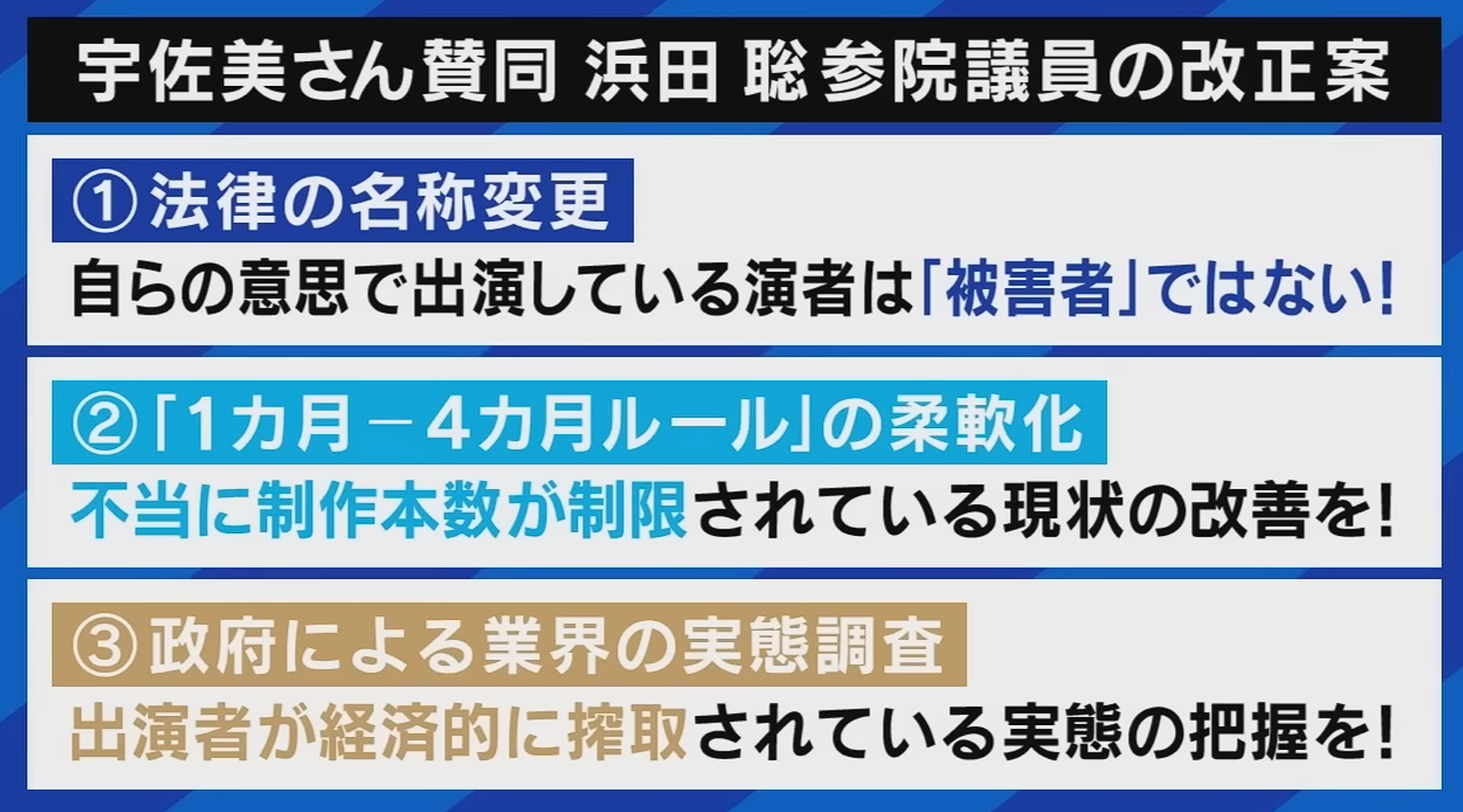

In response to the new AV law being enacted in a manner so detached from the reality of AV productions, ACOAVI’s second proposed amendment to the law in addition to flexibility of the cooldown period is a renaming of the law itself. The committee and its allies have stated that those who agree of their own volition to appear in adult films and clear the series of hurdles prior to filming cannot be correctly referred to as victims. The committee’s third suggestion is a government-sponsored investigation into the economic state and consent-related practices of the AV industry.

Speaking in an interview posted on YouTube on March 27th, AV actress Riko Hoshino noted the disparity in income between performers with exclusive studio contracts who film at least once a month (専属女優) and non-exclusive performers who often must network in order to be cast in films (企画単体女優). A government investigation into this issue would ideally identify methods to narrow this gap. In the same interview, Yoshiaki Nomoto, CEO of major AV studio Soft on Demand (SOD), stated that despite 18-year-old and 19-year old-performers being legally allowed to perform in AVs, SOD has refrained from casting performers under the age of 20, with performers who appear young only being marketed as 18 or 19 years of age as a promotional tactic. He expressed hopes that a government investigation would allow lawmakers to see such efforts to solely welcome informed, consenting adults into the AV industry.

Ways to help the campaign and the AV industry

The above Change.org petition can be signed privately and anonymously. If possible, please consider signing and sharing the petition. Those who wish to support the campaign’s efforts are strongly encouraged to purchase AVs through legal vendors, such as:

- ZENRA (English-language interface, not accessible within Japan)

- FANZA (Japanese-language interface)

- MGS動画 (Japanese-language interface)

- Duga (Japanese-language interface)

Lastly, please consider sending words of support to industry members whose work you enjoy via social media. In the midst of a law that dehumanizes AV industry professionals, the power of human connection cannot be underestimated.

Header: Image of ACOAVI’s March 8th protest in Shinjuku. Image credit: X/Twitter

Sources

- “Is Japan’s New Adult Video (AV) Law Working?” Unseen Japan

- 「AV新法」施行から2年…条項に“見直し”記載も検討せず?女優たちが異例のデモ 「法律がアングラに追い込んでいる」宇佐美典也氏が訴え Yahoo! News

- 【AV新法】現役女優が異例のデモ?法律のせいでアングラ化?見直しの検討は?しみけん&宇佐美典也と考える|アベプラ YouTube

- 国会議員、弁護士、教授ら有識者を招き、AV新法の見直しを検討するシンポジウムを開催しました 日刊SODオンライン

- AV新法を改正し、AV業界を崩壊の危機から救いたい Change.org

- テリー伊藤、銀座でセクシー女優らと「AV新法」改正デモ「たくさんの人が疑問を持っている」日刊スポーツ

- 【引退宣言⁉︎】「AV新法で面白味が激減」26年間のキャリアに疑問を持ち始めたしみけんさんの真意をメディア初告白。YouTube

- 【AV新法改正を熱く議論】「このままではAVはなくなる」第一回シンポジウム開催!国会議員、弁護士、教授ら有識者を招き、AV新法の見直しを検討(参加政党:自民、維新、国民、N国)YouTube

- 日本国憲法(昭和二十一年憲法) The Constitution of Japan (Constitution 1946) 日本法令外国語訳データベースシステム

- AVANってなに?AVAN (AV人権倫理機構 外局)

- 施行から2年…A●新法によって現場はどうなった?大手ビデオメーカーに現状を聞く YouTube